POSTES INTERNATIONALES DU MAROC

POSTES INTERNATIONALES DU MAROC

Hungering souls and “A Hunger Artist”

By Mohammed Hassissi – Tetouan

With the global Christmas mass shopping frenzy drawing near, Franz Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist” is as relevant as can be. The Czech novelist who wrote “The Trial” and “The Metamorphosis” baffles the reader yet again with a major piece that is a culmination of Kafkaesque fiction. Every word in this short story screams to be deciphered, and almost none would allow it. Yet, beneath the puzzle lies a terrifying truth and a subtle story for those with eyes to see; it is that of Man’s eternal and utter failure to transcend above materialism and the mundane and embrace a nobler and higher self.

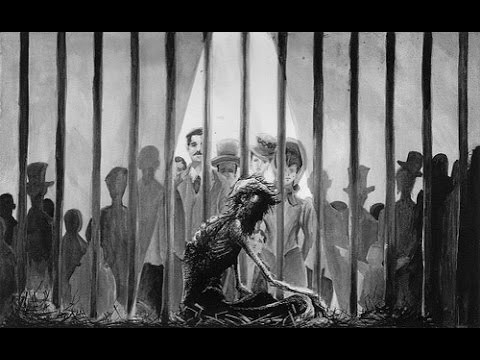

In a third-person retrospective narrative voice, the author tells the story of a self-starver who used to exhibit himself publicly in a cage to the amazement of many, the disdain of some, and the genuine admiration of few. The hunger artist, who was under the patronage of an impresario, was allowed to fast for a maximum period of forty days under the gaze of a baffled crowd—something which frustrated him as he always wished to extend that period so he may baffle that crowd even more. While he was as content as his audience was amazed and entertained, he was particularly vexed, however, at some “constant observers” who were “usually butchers”, and who were ever skeptical about the genuineness of his fast. Furthermore, the artist’s only brief and blissful content seemed to derive from the innocent bewilderment of children. The narrative hurriedly flows forward in time when interest in the hunger artist has diminished altogether, the impresario’s desperate attempts to find new audiences are in vain. Eventually, the self-starver and his impresario part ways and the former “let himself be hired by a large circus”. There, he is placed near “the animal stalls”. Now that he is free to fast as long as he wishes, no one finds his art worthwhile. Instead, people would rush past him to marvel at animals which “lacked nothing” and “enjoyed the taste” of food.

While Kafka’s writing is of no particular style or literary diction, what mesmerizes his reader is his use of the bizarrely untrue to capture a truth about ordinary people. To this end, Kafka is canny enough to take his metaphors literally. Just as in “The Metamorphosis”, he doesn’t merely tell us that Gregor Samsa feels as estranged as a cockroach in his father’s house, but that he wakes up one morning to find himself literally turned into one, here too, the ascetic is a self-starver who willingly locks himself in a cage before everyone to see, so that they may “admire” his fasting and come to witness that controlling one’s whims and desires is “the easiest thing in the world”. The artist never wants glory and appreciation for him, but for the act of fasting itself, as he blatantly confesses in the end “I always wanted you to admire my fasting”. In times of old, as the narrator reminisces, people did admire and look up to the ascetic, though there were always those watchers— butchers—who, unlike the self-denier, were voracious and self-indulgent, and were ever disdainfully skeptical about the authenticity

of the artist’s fast. In other words, the more we indulge in earthly pleasures, the more we reject and resent those who are closer than us to that noble and higher state of being.

The stark contrast between the transcendent and the base, and the terrific battle between the self-disciplined and the self-indulgent culminates towards the end of the story when interest in the art of fasting— self-restraint that is— dwindles to the point of zero. People rush straight past the “constantly diminishing obstacle”, and deliberately miss on an opportunity to reflect on a portrait of sobriety and abstinence. Instead, they would flock to marvel at the wild animal which hasn’t got the slightest reservation to wallow in and self-indulge; its instinct resonates with their human nature. In our modern times of ferocious capitalism, the ascetic is no longer looked up to, but rather resented, for he painfully reminds us of how we should be but can’t be. Unlike the ascetic who is so free he could lock himself up willingly, the modern man becomes a panther who neither needs freedom nor is he allowed one, but one who is allowed to have his fill (or lack of) of whims and pleasures.

Strangely enough, Kafka doesn’t end his story on such a fatalistic note. There is one character in the story who remained positively unchanged. Unlike the impresario and the circus manager, the butchers and circus guards, and worse of all, the spectators who grew cold and indifferent, the only ones who remained genuinely faithful to the artist and his art are children. Untarnished and pure, their persisting admiration reveals man’s innate inclination to aspire to the human rather than the beast in him and reminds us –adults—that if we were only to lead by example, one day our kids may not brawl and fistfight over a microwave on a black Friday.

One might argue that It would probably be too shallow to interpret the story of “The Hunger Artist” as one that sheds light on the struggle of the modern artist; It would be too exclusive. This, then, is a timeless and universal tale that stirs that eternal Armageddon within us— the instinctive inclination towards our base earthly pleasures and our moral obligation that ought to make us transcend the trivialities and refine our taste. Hence, the artist’s final words which he uttered with “firm, if no longer proud, conviction that he was continuing to fast” as he explained why he had been fasting: “I couldn’t find a food which I enjoyed”. This masterpiece of a short story is nothing short of a vivid reminder that we ought to stop living as beasts and start living as human beings instead.